The hallowed, often-chaotic halls of Holby City Hospital’s Emergency Department are no strangers to drama, but rarely does a shift descend into such a searing indictment of professional conduct and systemic pressures as witnessed in a recent, pivotal episode of BBC’s long-running medical drama, Casualty. Under the stark, unforgiving fluorescent lights, a harrowing incident unfolded, leaving a patient teetering on the brink of death and exposing the perilous tightrope walked by dedicated healthcare professionals – a tightrope that, for one nurse, snapped under the weight of personal demons and the relentless grind of “supply and demand.”

The episode, an emotional and ethical maelstrom, centered squarely on Nurse Ngozi Okonjo, whose early morning arrival at work set an unsettlingly low bar for the day. The unmistakable sounds of violent retching emanating from a staff restroom echoed through the quiet pre-shift preparations, a grim overture to the professional nightmare that was about to engulf the department. Ngozi, emerging pale and disheveled, attempted a flimsy façade of normalcy, blaming her distress on a rogue breakfast. But her colleague, the astute and observant Nicole, saw through the flimsy charade with a single, knowing glance: Ngozi was profoundly, debilitatingly hungover.

This wasn’t merely a minor indiscretion; in a high-stakes environment where seconds and precision define the line between life and death, Ngozi’s impairment was a ticking time bomb. The implied narrative is chilling: how many times had this happened? How many patients might have been unknowingly under the care of a nurse whose judgment was clouded, whose reactions were dulled by the lingering effects of alcohol? It’s a question that Casualty, renowned for its unflinching portrayal of NHS realities, bravely dares to pose, forcing viewers to confront the human cost of an overburdened system.

The immediate casualty of Ngozi’s compromised state was Mr. Riley, a sweet, elderly patient presenting with chest pain. His vulnerability was heartbreakingly amplified by his simple, earnest hope: to attend his granddaughter’s birthday party, an invitation he cherishes as a rare beacon of family connection. Ngozi, seemingly distracted and dismissive, offered platitudes and a promise to get him to CT, her focus clearly fragmented. It was a critical juncture, a moment that demanded sharp clinical observation and swift action, yet it was tragically, fatally, missed.

As Mr. Riley’s condition deteriorated, a ripple of unease spread through the ED. Nicole, sensing the gravity of the situation and perhaps a subconscious concern for Ngozi’s competency, stepped in. She volunteered to take Mr. Riley for his crucial CT scan, offering to cover for her clearly struggling colleague. It was an act of collegial support, born from a desire to keep the wheels of patient care turning, but it inadvertently entangled her in Ngozi’s professional downfall. Nicole’s subsequent request for a simple bilateral blood pressure reading – a standard, yet vital, diagnostic step – was the last hope for an early detection.

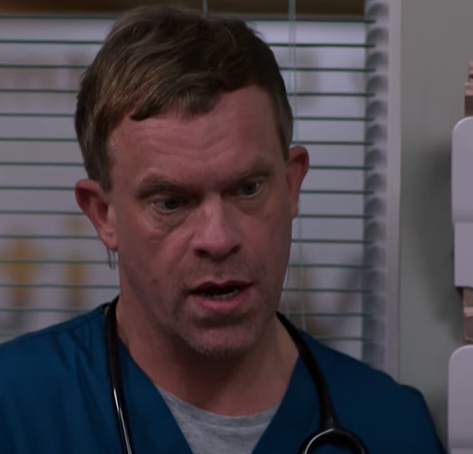

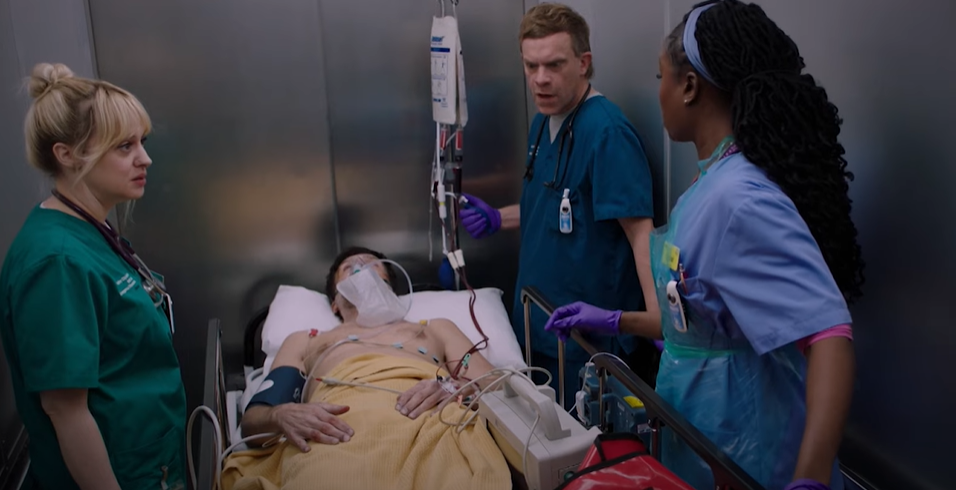

The dramatic tension ratcheted up when Clinical Lead Dylan Keogh, ever the hawk-eyed overseer, discovered Mr. Riley still waiting, his CT scan inexplicably delayed. Dylan’s growing concern quickly morphed into alarm as he personally reviewed Mr. Riley’s charts. The horror of the situation became chillingly clear: Mr. Riley was suffering from an aortic dissection, a catastrophic tear in the body’s main artery, a condition requiring immediate, life-saving intervention. The missed opportunity, the perilous delay, was a direct consequence of the initial diagnostic failure – a failure inextricably linked to Ngozi’s impairment.

The scene escalated into a frantic battle against time. As Mr. Riley’s Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score plummeted, indicating a rapidly deteriorating neurological state, the ED transformed into a maelstrom of urgent medical intervention. Dylan, his voice tight with controlled fury, demanded answers, questioning the bilateral readings, the very data points that should have screamed “aortic dissection” to any attentive clinician. The damning disparity – 160/94 on one side, 126/42 on the other – was the smoking gun, irrefutable proof of a missed opportunity, a glaring oversight.

What followed was an almost unbearable disciplinary meeting, convened by Dylan and Dr. Keogh, their faces etched with grave disappointment. Mr. Riley, through sheer surgical brilliance and a slice of luck, survived. The emergency CT revealed a Category B tear, swiftly repaired. But his survival did not absolve the nurses of their grievous error. The air in the room crackled with accusation and defensiveness as Dylan laid bare the core issue: “A serious mistake was made today that jeopardised patient care.”

The “blame game” that erupted between Ngozi and Nicole was raw and visceral. Ngozi, true to her earlier denial, immediately deflected, throwing Nicole under the bus. “He was not my patient. He was Nicole’s,” she spat, conveniently forgetting her initial responsibility and Nicole’s act of assistance. Nicole, understandably furious at being scapegoated, retorted with equal ferocity, reminding Ngozi of her offer to help, of Ngozi’s own “failings.” Dylan, cutting through the vitriol, slammed his hand down, delivering a stark truth: “You both made mistakes. OK?”

While Nicole offered a remorseful apology, Ngozi’s concession was notably absent of genuine regret, a mere echo of Nicole’s words. This defiant lack of accountability, this persistent self-preservation, painted a stark portrait of a character wrestling with deeply ingrained issues. Dylan’s attempt to “draw a line under it” felt less like a resolution and more like a temporary ceasefire, a necessary pause before the next inevitable conflict.

The episode culminated in a chilling, private confrontation between Dylan and Ngozi. Dylan, clearly aware that the hangover was not an isolated incident but a symptom of a deeper problem, urged Ngozi to attend a meeting – an unspoken suggestion of support groups or professional help. Ngozi’s response was a defiant, almost desperate, refusal. “I don’t have a problem,” she insisted, her voice tight with denial. “If you don’t believe me, you can breathalyse me every shift. I don’t care.” It was a desperate challenge, a defensive wall built against intervention, suggesting a profound struggle with addiction or a dangerously unhealthy coping mechanism.

This storyline brilliantly weaves into the broader “Supply and Demand” narrative that underpins much of Casualty’s enduring appeal. The “demand” on healthcare professionals is relentless: long hours, emotional fatigue, exposure to trauma, and the constant pressure of understaffing and dwindling resources. The “supply” of resilient, unflappable nurses and doctors is finite, and even the most dedicated can be pushed to breaking point. Ngozi’s case, while extreme, serves as a poignant, if uncomfortable, exploration of what happens when the professional demands outstrip the individual’s capacity to supply, leading to burnout, self-medication, and ultimately, catastrophic errors.

Casualty once again proves its mettle, not just as a medical drama, but as a socio-critical commentary. It peels back the veneer of heroism to reveal the profound human frailties of those we entrust with our lives. Ngozi’s story is a stark warning: beneath the scrubs and the professional veneer, there are individuals battling their own silent wars. And when those wars spill into the workplace, the consequences, as Mr. Riley so nearly discovered, can be devastating. The question now looms large over Holby: what will it take for Ngozi to confront her demons, and what further casualties will there be before she does? The stage is set for a gripping, and potentially tragic, continuation of her journey.